These miserable old stories

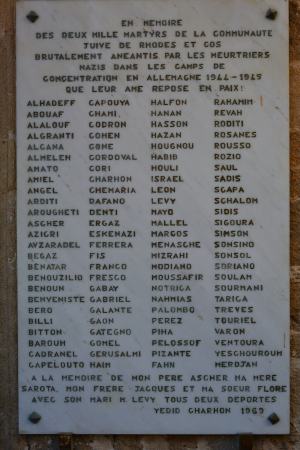

It is the end of March. I am wandering around the medieval part of the city of Rhodes – which is somewhat lazily called the Old Town. The narrow streets are eerily deserted and will remain so for some time. The tourists arrive later and later these days. In Dimokratiki newspaper nervous hotel owners are contemplating whether they dare open for Easter. People are glancing around for suitable escape routes. The feeling of being on a sinking ship leads to many taking to the lifeboats too early. I approach the Jewish quarter – La Juderia – and although few places can make me feel more gloomy, a thought strikes me, one as stubborn as it is trivial, which suggests there ought to be a Jewish taverna hereabouts. That would be appropriate. There cannot be a more hopeful cuisine than that of the Jews of Rhodes. They quickly adopted all that made sense from Greek and Turkish traditions, blending Romaniote cuisine with a variety of Spanish comidas, and when one finds dishes such as yaprakes, boyos and biscochos de huevo in the same tradition, one realizes the result is a cuisine far greater than the sum of its parts. But the only people who can prepare these dishes today live in New York, and the tourists – who could do with a rest as they reach the Holocaust memorial – only have time to cool down with a soft drink before the tour of the wonders of the Knights Hospitallers begins.

Dark Clouds

Ever since it was founded in 409 BC, the city of Rhodes has played a key role in virtually the entire history of Europe and the Mediterranean. Yet all one hears about these days are the Knights Hospitallers. The great fascination with these industrious knights stems largely from the work of the preposterous Italian governor De Vecchi. This little man and his unparalleled self-image would be truly comical were it not for the fact that as soon as he arrived in December 1936 he began to plunder the island of its entire resources, including its history. Nowhere did the fascist idea of rebirth impact so catastrophically on the cultural heritage of an entire island as here. Most things on Rhodes are fake. The ‘medieval’ Palace of the Grand Master, which attracts huge numbers of tourists, is one of De Vecchi’s inventions. It is really nothing more than worthless fascist kitsch, about as historically authentic as the backdrop for some comic opera. The Italian archaeologists who worked for Mario Lago, De Vecchi’s less obtrusive predecessor, complained that most things De Vecchi did were a complete disaster. De Vecchi was well aware of this, but it did not bother him. He considered his greatest achievement, for want of anything better, to have been the persecution of the island’s Jews. The deeply religious De Vecchi is a prime example that the persecutors of Aegean Jews have nearly always been Roman Catholics rather than Muslims or Greek Orthodox Christians. When he arrived on Rhodes in 1936 there were four thousand Jews on the island. When he left, none remained.

Jews have always lived on Rhodes, and they have always been persecuted. For example, in 1522 Rachel Granada caught the knight d’Amaral passing secrets to the Turks, but was herself executed for the crime. However, Jews have also been loved and respected, as in the case of Boaz Menasché Effendi or Raḥamim Judah. The Hospitallers established themselves on the island in 1309. Their plan to ‘recover’ the Holy Land naturally did not include the Jews, and facing increasingly stiff resistance from the Muslims the knights increased their reprisals – against the Jews. And so the knights continued. They fought, built and toiled, negotiated, persecuted, and built some more – all with a strange kind of patience. Just when the Turkish commander started to tire of them and thought of returning home, the crusaders – the same warriors hailed today as military geniuses – raised the flag of surrender. They sailed to Malta and never returned. The Turks could scarcely believe their eyes. The Jews breathed a sigh of relief.

For the next 390 years Rhodes was part of the Ottoman Empire, an era portrayed by some as idyllic – which in the beginning it virtually was – but described by others as indolent, capricious and cruel – which it would later become. Perhaps the feeling of a shared fate explains the keenness of the Greeks for pointing out their strong ties with the Jews – and if one forgives a certain smugness with regard to the book Documents on the History of the Greek Jews – they do indeed have every reason to feel proud.

For the next 390 years Rhodes was part of the Ottoman Empire, an era portrayed by some as idyllic – which in the beginning it virtually was – but described by others as indolent, capricious and cruel – which it would later become. Perhaps the feeling of a shared fate explains the keenness of the Greeks for pointing out their strong ties with the Jews – and if one forgives a certain smugness with regard to the book Documents on the History of the Greek Jews – they do indeed have every reason to feel proud.

To analyse the many accounts of Rhodian Jewish history should be straightforward. But as in practically all cases concerning Jews, one must work much harder, primarily to get to know the author much better, than would otherwise be necessary. For example, a relatively simple task – to gain an idea of personal economic conditions – can be problematic. Jews are portrayed as destitute often to stress their idleness rather than their misery, and an author who frequently mentions wealth probably aims to reveal their cunning in exploiting their neighbours. Moreover, fickleness on the part of the nineteenth-century authors who described the Levant can be treacherous – one needs to know exactly when they were writing. But in the case of Rhodes we are in luck. In about 1840 we know the Jewish population included ten shoemakers, six tailors, one perfumer, a handful of barbers, a few dragomen – interpreters at the European consulates – and that certain affluent families traded in sponges, wine, silk and coffee, among other things. In other words, some were poor, some made a healthy living, and some were rich – which sounds obvious really, but which evidently needed saying in the case of Jews. This, in any case, was the situation in the winter of 1840.

The Rhodes blood libel

On 17 February 1840 the Jews of Rhodes were accused of the kidnap and ritual murder of a child. The little boy had disappeared somewhere on the road between Trianda and the city of Rhodes, and someone claimed to have seen him in the company of three Jewish men. Immediately several influential figures began to spread a rumour – the Jews had killed the boy to use his blood. Ever since the time of Moses, they said, the making of Passover bread had required the ritual murder of a Christian. When the chief rabbi enquired where on earth Moses would have obtained Christian blood, they replied the answer was so obvious it was not worth discussing. Then they tortured him. Several contemporary accounts describe the events that followed. Although they rarely agree, we do know that the accused were brutally tortured and that the Jewish quarter was blockaded for twelve days. The inhabitants thirsted and starved and were subjected to continual night-time raids. La Juderia was virtually besieged until the end of August. This tragedy, along with others that by strange coincidence happened at roughly the same time in Scala Nova (present-day Kuşadasi), on Chios, and in Smyrna, for example, has been overshadowed by the more famous Damascus affair – as discussed by Jonathan Frankel – but aside from the diplomatic repercussions of the latter, the charges in all places were largely identical. But there is also one significant difference. If one thing characterizes the events on Rhodes it is the unusual way in which resistance was mobilized. The Jews on Rhodes reacted with lightning speed. Within just a few days the news had reached the European foreign ministries, allowing the leading British, French and German newspapers to provide their readers with detailed coverage. Briton Sir Moses Montefiore and Frenchman Adolphe Crémieux worked vigorously to free the Jews. They succeeded, thanks largely to the great support of the Muslim theologians who petitioned the Sultan, who in turn issued a decree refuting the charges, forbidding anti-Semitism, and affording the Jews the full protection of the Ottoman Empire.

Afterwards the Turkish governor was held partly responsible for the tragedy on Rhodes but most of the blame was levelled at the Greeks. Even if the former tortured liberally and the latter did not seem to mind, nothing changes the fact that the governor was working under great pressure, and that the Greeks, only four of whom were tried, seemed unconvinced by the allegations against the Jews. Moreover, the waters of guilt are muddied because the charges against the Jews had been drawn up by the real villains. On Rhodes certain figures had distinguished themselves by instigating the trial and taking part in the torture – primarily the British, Austro-Hungarian and Swedish vice-consuls.

The warriors of Odin

Because peculiar ideas about a Nordic identity ‘legitimized’ the murder of six million Jews, the events on Rhodes are usually ascribed to the prehistory of the Holocaust, where this philosophy, even as an embryo, showed its true nature. The behaviour of the Swedish vice-consul should therefore come as no surprise. This conclusion is too simplistic. The nationalities of the vice-consuls actually tell us nothing (the union of brothers – Sweden and Norway – had a Belgian vice-consul), and we must bear in mind that London and Vienna provided the Jews with their strongest support. Moreover, this philosophy had yet to take hold in Sweden – if it ever did – which perhaps explains the indignant reaction of the Swedish press. A warrior of Odin, one journalist wrote, would never have mistreated Jews because he himself was a child of Israel too.

The events on Rhodes, and reactions to them, contain several key elements that relate equally to a Scandinavian view of itself as to an idealized, Scandinavian relationship with the rest of the world. At this date an older, popular Scandinavian notion of antiquity still prevailed, one that had always identified itself with the people of Israel. Regardless of whether we turn to rune stones, or to travel books from the fourteenth or early eighteenth centuries, we find this to be a widespread idea. Some scholars have argued that Gothicism and its later descendent Germanism played a central role in creating the modern Swedish identity. But this theory is problematic. Gothicism, even at its height, was the domain of a select group of academics and aristocrats, and even here Germanism was clearly subordinate to anti-German Scandinavianism. To state that a warrior of Odin would never have been anti-Semitic therefore reflects the spirit of the age. A half century would elapse before the warriors of Odin, along with all other ancient Swedes, became transformed into incorrigible, violent barbarians with an insatiable bloodlust, and for antiquity to become one endless torchlight procession in which Germanic peoples devoted themselves to meting out intuitive justice – all in the interests of promoting the race.

As we have seen, the Swedish press reacted indignantly to the charges. The persecution stemmed from ‘the false allegations of fanatics’. Aftonbladet thought the accusations ‘highly improbable’, publishing in full Crémieux’s eloquent letter to the French people – which proved to be something of a turning point for the anti-Semitic French clergy too.

The Swedish government reacted somewhat differently. In November Stockholm declared that the events which had captivated the whole of Europe had in fact never happened. A Swede, it admitted, might have been involved in a similar incident in Scala Nova, but there was no link with Rhodes. Because the Swedish vice-consul on Rhodes was the same official who had persecuted the Jews in Scala Nova, the British reacted with unusual irritation. The Foreign Minister Lord Palmerston, having intervened forcibly against his own vice-consul, now demanded to know why the Swedes had failed to do the same with theirs. However, the problem stemmed not from malicious intent but from unparalleled confusion at the newly formed Swedish Foreign Ministry – Stockholm was quite unable to remember the names of all its vice-consuls.

The actions of the vice-consuls may be interpreted in various ways, but as an archaeologist I cannot help noticing something that may seem trivial. Many of the most enthusiastic participants in the torture – here and on later occasions – are today considered great ‘connoisseurs’ of classical antiquities, who eagerly collected anything from potsherds to whole temples. Coincidentally, so too were some of the accused. Many collectors and custodians of antiquities and monuments in this part of the Mediterranean were Jewish intellectuals. The plundering of their homes and businesses led to numerous antiquities ‘changing owner’. Not a few ended up in Swedish hands, and some are almost certainly in Swedish museums today.

Islanders

For island inhabitants history serves no didactic function. Whatever happened has happened, and even if islanders recall unhappy events with little enthusiasm, they are forced to live with them forever. Coop with it or sail somewhere else. The history of Rhodes is the history of the islanders themselves, and to avoid oneself is, after all, impossible. The Greek intellectuals with whom I have spoken never deny that Greek Orthodox passivity influenced the events on Rhodes. But they become far happier when talking about something else – the Jewish resistance! The Jews did not just sit down and write subservient letters. They took to their fists and put up a fight. This sort of thing always impresses the Greeks. With due respect to the diplomatic process, it would be foolish to ignore the role active resistance played in securing a positive outcome.

We cannot end our story without mentioning that the little boy, the one claimed to have been ritually murdered, later turned up unharmed on the island of Syros. This historical fact contains an inherent drama: Syros, dominated by European Roman Catholics, was out of bounds for Jews, a most suitable place to hide a supposed ritual-murder victim. According to a less conspiratorial account, the boy had simply become angry with his mother and travelled to Syros to find his much kinder father.